The Science of Land-Use Change in New England is a Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands, and Communities initiative that studies the long-term changes in forest ecosystems in New England with a focus on quantifying how changes in land use — including timber harvest, land conversion, and conservation — affect the benefits that landscapes provide now and in the future.

Harvard Forest Senior Ecologist Jonathan Thompson is a key collaborator in the robust science that this initiative brings to land conservation and policy. Thompson is a forest landscape ecologist who studies long-term changes in forest ecosystems. His work in New England is especially focused on quantifying how changes in land use — including timber harvest, land conversion, and conservation — affect the benefits that landscapes provide now and in the future.

Recovery from Colonial Era Land Use Will Drive Changes into the Future

Following widespread deforestation for agriculture during colonial times, the slow and steady recovery of New England’s forests continues as an important landscape dynamic today. Using a landscape model that simulates future forest dynamics (tree competition for light, water, and nutrients, for example), Thompson and his research team have determined that, in the hypothetical absence of pests and future land use, this recovery from deforestation would be the strongest driver of forest species change and growth dynamics, playing an even stronger role than climate change.

400 Years of Land-Use Change Has Benefited Some Species and Not Others

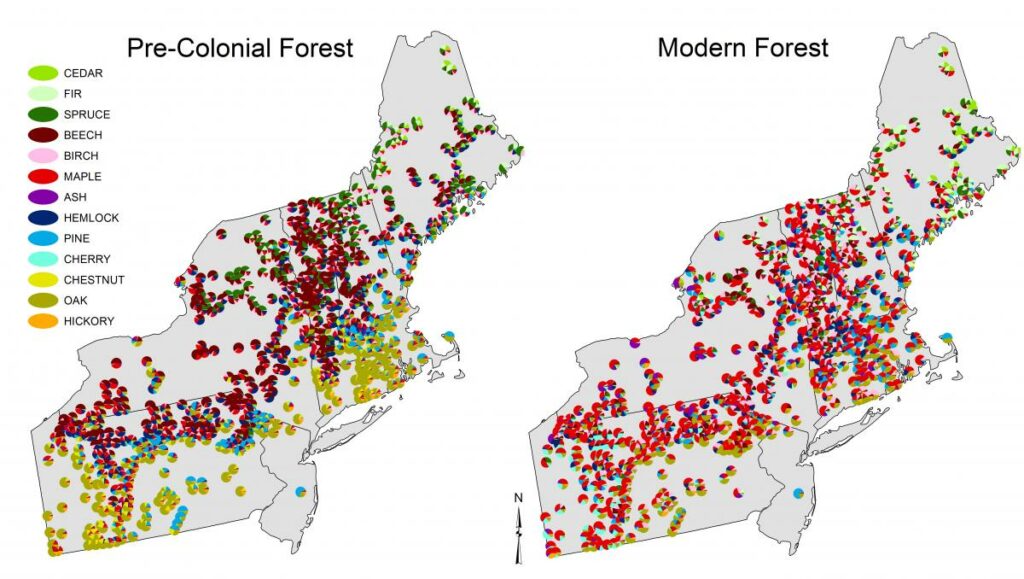

In 2013, Thompson and his team compared records of forest composition from pre-colonial surveys to modern data and found that the 400-year history of land use benefited maple the most. Maple is now a dominant tree type throughout most of the region. Short-lived, early seral species such as birch are also much more common in the modern landscape.

Late successional trees, such as beech, hemlock, and spruce, that were once predominant across the region, are now much less so, save for in some small refugia within isolated mountain regions with little history of land use. Oak has also declined throughout most, but not all, of its range.

“On the one hand,” says Thompson, “the modern expense of forest is diminished in so many of the components and processes that once characterized the regional ecosystem; on the other, given the extent and magnitude of land use, it is remarkable that native species predominate and the forests looks in many ways as it has for millennia.”

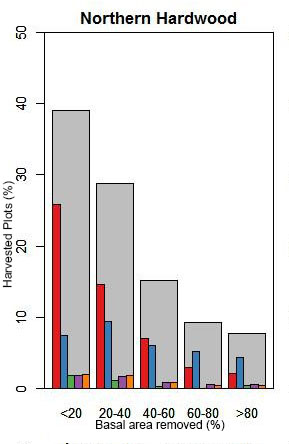

When It Comes to Timber Harvest, Land Ownership Matters

Family forest owners cut almost as frequently, but much less intensely, than corporate owners, according to a 2017 study that integrated results from the US Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis database with U.S. Census and National Woodland Owner Survey (NWOS) data. Corporate, state, and municipal forests in the Northeast all have similar distributions of harvest intensity: the median percentage of basal area removed from those forests during harvest events is approximately 40 percent. When family forest owners harvest, they tend to harvest a smaller proportion of the wood (see “FFO” in red in the graph at left).